Understanding LLM Evaluation Metrics: Best Practices for Reliable LLM Assessment

As organizations adopt Large Language Models (LLMs) across customer service, marketing, research, and product development, rigorous evaluation of these models becomes a business-critical capability. Poorly evaluated models can lead to misleading outputs, legal liabilities, and damaged user trust. Stakeholders ranging from data scientists and ML engineers to product managers and compliance teams need to understand how to measure LLM performance, reliability, and fitness for production.

This post dives deep into the most widely used LLM evaluation metrics, what they measure, how they work, where their limitations are, and when to use them.

1. Perplexity

What It Is

Perplexity is a standard metric in language modeling that quantifies how well a language model (LM) predicts a sequence of tokens. In simple terms, it measures how “confused” the model is when generating text: the lower the perplexity, the better the model is at predicting what comes next.

Intuition

If a model assigns high probability to the correct next token, it means the model is confident and not “perplexed”, resulting in low perplexity. Conversely, if the model spreads its probability mass across many wrong options, perplexity will be high.

You can think of it like this:

- A perplexity of 1 means the model is perfectly confident, it always predicts the correct next word.

- A perplexity of 10 means the model is, on average, as uncertain as if it had to pick randomly from 10 equally likely next words.

Formula

\[\text{Perplexity} = 2^{-\frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \log_2 P(x_i)}\]where

- \(N\): Total number of tokens in the evaluation set

- \(x_i\): The \(i\)-th token in the sequence

- \(P(x_i)\): The probability that the model assigns to the true next token \(x_i\)

- \(\log_2\): Logarithm base 2 (used for interpretability in bits)

- The formula computes the negative average log-likelihood, then exponentiates it to return to probability space

The base 2 logarithm means perplexity is expressed in terms of bits, as in “how many bits of uncertainty” the model has.

How to Test It

- Choose a held-out test set of tokenized text.

- Use your trained language model to calculate the probability of each token in the sequence.

- Apply the formula above to compute the perplexity score.

Popular libraries like HuggingFace Transformers and OpenLM provide built-in utilities to compute perplexity.

Business Example

Imagine you’re a product manager evaluating which LLM to fine-tune for internal knowledge search. You compute perplexity on your company’s corpus using two models:

- GPT-3: perplexity = 15.2

- Claude: perplexity = 12.7

Claude’s lower perplexity means it’s better at modeling your internal documents and will likely produce more fluent and relevant completions.

Limitations

- Doesn’t measure factual accuracy: A model may be fluent but confidently wrong.

- Not task-specific: Doesn’t capture how well a model performs in classification, QA, or summarization.

- Sensitive to tokenizer choices: Different tokenization schemes yield different perplexity scores.

When to Use

- During pretraining or fine-tuning to monitor convergence.

- Comparing base model quality before choosing one for downstream tasks.

- Tracking improvements across language modeling benchmarks (e.g., WikiText, Penn Treebank).

2. Exact Match (EM)

What It Is

Exact Match (EM) is one of the simplest yet most stringent metrics used in evaluating language model outputs. It checks whether the predicted output matches the reference (ground truth) exactly. If they match perfectly, the score is 1; otherwise, it is 0.

Intuition

Imagine asking a model: “What is the capital of France?” If the model responds with “Paris,” that’s a perfect match. If it says “The capital of France is Paris,” or just “paris” (lowercase), that may still be correct in meaning, but EM will give it a 0 if the formatting isn’t identical.

Thus, EM is ideal when you require precision and can’t tolerate variation in wording or structure.

Formula

\[EM = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{N} \mathbb{1}[y_i = \hat{y}_i]}{N}\]where

- \(N\): Total number of test examples.

- \(y_i\): Ground truth (correct output) for the \(i\)-th example.

- \(\hat{y}_i\): Model’s prediction for the \(i\)-th example.

- \(\mathbb{1}[\cdot]\): Indicator function, it returns 1 if the condition is true (exact match), and 0 otherwise.

This formula counts how many predictions are exactly correct, then divides by the total number of predictions.

How to Test It

- Prepare a set of ground truth answers for your task.

- Generate model predictions for the same inputs.

- Apply the EM formula by comparing each prediction to its corresponding ground truth.

You may also want to normalize the text before comparison (e.g., remove punctuation, lowercase, strip whitespace) depending on your use case.

Business Example

📨 Invoice Processing: A company builds an LLM to extract invoice numbers from customer emails. Since invoice numbers must match exactly (e.g., “INV-20394”), EM is used to measure how often the model extracts the exact string correctly.

- Ground truth: “INV-20394”

- Prediction: “INV-20394” → EM = 1

- Prediction: “INV20394” → EM = 0 (even though it looks similar)

Limitations

- Overly strict: Penalizes answers that are semantically correct but phrased differently.

- Insensitive to formatting differences: Minor variations in punctuation or casing result in a zero score.

- Binary outcome: Doesn’t tell you how wrong the prediction is , only if it’s perfect or not.

When to Use

- For closed-domain QA or extraction tasks with highly structured outputs.

- When exact correctness is critical (e.g., usernames, codes, numeric answers).

- In early-stage benchmarking where strict matching is acceptable for diagnostic purposes.

3. BLEU / ROUGE / METEOR

What They Are

These are n-gram overlap metrics widely used to evaluate text generation tasks such as machine translation, summarization, and text rewriting.

- BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy): Measures precision, how many predicted n-grams appear in the reference.

- ROUGE (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation): Measures recall, how many reference n-grams appear in the predicted output.

- METEOR (Metric for Evaluation of Translation with Explicit ORdering): Combines precision + recall with additional features like stemming and synonym matching.

Intuition

Imagine the model’s output is a guess and the reference is the gold answer.

- BLEU rewards guesses that match many parts (n-grams) of the gold answer

- ROUGE emphasizes capturing all the key content from the reference.

- METEOR tries to balance both while being more linguistically sensitive.

BLEU Formula

\[BLEU = BP \cdot \exp\left( \sum_{n=1}^N w_n \log p_n \right)\]where

- \(BP\): Brevity penalty, discourages overly short translations

- \(N\): Maximum n-gram size (commonly 4)

- \(w_n\): Weight for n-gram of size \(n\); often uniform (\(w_n = 1/N\))

- \(p_n\): Precision of n-grams of size \(n\) (e.g., how many bigrams in prediction match the reference)

- \(\log p_n\): Logarithmic transformation to prevent a single zero from nullifying the score

ROUGE Formula (ROUGE-N)

\[ROUGE\text{-}N = \frac{\sum_{S \in \text{Reference}} \sum_{gram_n \in S} \text{Count}_{match}(gram_n)}{\sum_{S \in \text{Reference}} \sum_{gram_n \in S} \text{Count}(gram_n)}\]where

- \(gram_n\): An n-gram sequence

- \(\text{Count}_{match}(gram_n)\): Number of overlapping n-grams between prediction and reference

- \(\text{Count}(gram_n)\): Total number of n-grams in the reference

METEOR Formula (Simplified)

\[METEOR = F_{mean} \cdot (1 - Penalty)\]where:

- \[F_{mean} = \frac{10 \cdot P \cdot R}{R + 9P}\]

- \(P\): Precision (matched unigrams / total unigrams in candidate)

- \(R\): Recall (matched unigrams / total unigrams in reference)

- \(Penalty\): Penalty for fragmented matches (e.g., out-of-order tokens)

How to Test It

- Generate model output for a test set.

- Compare each output to one or more reference texts.

- Compute overlapping n-grams at different sizes (1-gram to 4-gram).

- Use libraries like

sacrebleu,nltk.translate, orevaluate(from HuggingFace) to calculate BLEU, ROUGE, and METEOR scores.

Business Example

🛍️ E-commerce Product Descriptions: A retailer uses LLMs to auto-generate product descriptions. To evaluate fluency and informativeness:

- Human-written descriptions are used as reference.

- BLEU and ROUGE scores are computed for generated content.

- METEOR is also considered to capture variations like “soft cotton shirt” vs. “cotton shirt with a soft feel.”

Limitations

- Surface-level matching: Cannot account for paraphrasing or different correct phrasings.

- Sensitive to exact word order (especially BLEU).

- METEOR is more flexible, but slower to compute and language-dependent.

When to Use

- Use BLEU, ROUGE, or METEOR when you have one or more human-written reference texts and you want to measure how closely the model’s output matches them in terms of word choice, phrasing, and structure. These metrics are especially useful for tasks where fluency, wording, and format are important, such as marketing content, translations, or summaries intended for publication.

-

For tasks like:

- Summarization

- Translation/localization

- Marketing copy generation

- Headline rewriting

4. BERTScore

What It Is

BERTScore is a metric that evaluates the quality of generated text by measuring semantic similarity between the candidate output and the reference using pre-trained contextual embeddings (usually from BERT or RoBERTa).

Unlike traditional n-gram overlap metrics (like BLEU or ROUGE), BERTScore can detect when the model’s output has the same meaning as the reference even if the words are different.

Intuition

Instead of looking for exact word matches, BERTScore embeds every word in the candidate and reference into a high-dimensional space using a pre-trained language model. It then computes how close these embeddings are, word by word, using cosine similarity. The closer the match, the better the semantic alignment.

Formula

\[\text{BERTScore} = \frac{1}{|\hat{y}|} \sum_{\hat{w} \in \hat{y}} \max_{w \in y} \text{cosine}_{sim}(\text{embed}(\hat{w}), \text{embed}(w))\]Symbols Explained:

- \(\hat{y}\): The generated (candidate) sentence.

- \(y\): The reference sentence.

- \(\hat{w}\), \(w\): Words in the candidate and reference respectively.

- \(\text{embed}(\cdot)\): Embedding of a word using a contextual language model (e.g., BERT).

- \(\text{cosine}_{sim}(a, b)\): Cosine similarity between two vectors \(a\) and \(b\).

- The final score aggregates how well each word in the candidate matches the most similar word in the reference.

How to Test It

- Tokenize and embed both the candidate and reference sentences using a BERT-based model.

- Compute cosine similarity between each token in the candidate and every token in the reference.

- For each candidate token, select the maximum similarity score.

- Average these maximum scores to get the final BERTScore.

You can use the bert-score Python package (https://github.com/Tiiiger/bert_score) for easy implementation.

Business Example

💬 Customer Support QA: A company builds an LLM-based assistant to answer customer questions using internal documents.

- Ground truth answer: “You can reset your password in the account settings section.”

- Generated answer: “Head to your profile settings to change your password.”

These answers are semantically the same, though not word-for-word matches. BERTScore recognizes this alignment, while BLEU or ROUGE may penalize the variation.

Limitations

- Computationally expensive: Requires embedding large numbers of tokens and computing pairwise similarity.

- Model-dependent: Results vary depending on the embedding model used.

- No structural understanding: Doesn’t account for grammar or sentence structure.

When to Use

- When semantic correctness matters more than surface form.

-

For tasks like:

- Answer validation in QA systems

- Paraphrase detection

- Summary evaluation

- Semantic search result comparison

5. Human Judgment

What It Is

Human judgment refers to evaluating language model outputs using human annotators who assess the quality of generated responses along various subjective dimensions. These can include:

- Relevance: How well the response answers the question or meets the prompt

- Helpfulness: Whether the information is actually useful to the user

- Factual accuracy: Is the content correct?

- Clarity: Is the text easy to understand?

- Tone/Style: Does the response match the required tone or brand voice?

This is considered the gold standard for evaluating open-ended generative tasks.

Intuition

Unlike automated metrics that compare outputs numerically, human judgment captures qualitative nuances. This includes subtle errors, logical coherence, and appropriateness that machines might miss. It enables real-world usability evaluation.

How to Test It

There are several common setups for human evaluations:

-

Likert Scale Rating:

- Annotators rate outputs on a fixed scale (e.g., 1–5 or 1–7).

- Example: “Rate this summary for informativeness.”

-

Pairwise Comparison:

- Annotators are shown two outputs for the same input and asked: “Which is better?”

- Often used in A/B testing to compare different models or prompting techniques.

-

Ranking or Point Allocation:

- Annotators rank multiple outputs or assign points proportionally.

-

Task-Specific Criteria:

- Create rubrics tailored to domain needs (e.g., legal clarity, medical safety).

-

User Studies:

- Evaluate with end users in real settings; observe satisfaction or task success.

Business Example

⚖️ Legal Tech Application: A firm is developing an AI tool to generate legal clause summaries. They run a blind study with 5 legal professionals:

- Task: Rate LLM-generated summaries of contract clauses on clarity and correctness.

- Method: Each participant scores outputs on a 5-point Likert scale.

- Outcome: Helps the team fine-tune the model and validate its readiness for production.

Limitations

- Subjective: Ratings can vary across annotators; inter-rater agreement must be tracked.

- Expensive: Involves human time and domain expertise.

- Slow: Difficult to scale to thousands of samples.

- Not reproducible: Results depend on who the raters are.

When to Use

- High-stakes applications (e.g., law, healthcare, education)

- Creative or generative tasks (e.g., storytelling, marketing copy)

- When automated metrics are insufficient or unreliable

- User experience validation in production systems

Best Practices

- Use multiple annotators and measure inter-annotator agreement (e.g., using Cohen’s kappa).

- Randomize and anonymize samples to avoid bias.

- Design clear, consistent rubrics.

- Combine with automated metrics for hybrid evaluation pipelines.

6. LLM-as-a-Judge

What It Is

LLM-as-a-Judge is a scalable, automated method for evaluating language model outputs using another large language model (LLM) to score, rate, or compare candidate outputs. The evaluator LLM is prompted to act as a reviewer or critic, assessing the quality of model responses across various dimensions like correctness, fluency, and helpfulness.

This is particularly useful in fast iteration cycles and large-scale experiments where human evaluation would be too slow or costly.

Intuition

Instead of relying on human annotators, you ask a trusted LLM (e.g., GPT-4, Claude, or Gemini) to act like a judge:

- It reads multiple outputs for the same prompt

- It scores or ranks them

- It explains why one output may be better than another

This approach leverages the evaluator model’s understanding of language, reasoning, and task alignment to mimic human judgment.

How to Test It

There are multiple setups depending on your needs:

1. Scoring (Point-wise)

- Prompt: “Score the following response from 1 to 5 based on factual accuracy.”

- Output: Numeric score + explanation (optional)

2. Pairwise Comparison (Relative Ranking)

- Prompt: “Here are two answers to the same question. Which one is better and why?”

- Output: Preference + rationale

3. Rubric-Based Evaluation

- Prompt: Provide specific criteria such as clarity, tone, correctness

- Output: Multi-attribute scores or classifications

You can use templates or frameworks like OpenAI’s Evals, LMSYS’s Chatbot Arena, or Anthropic’s preference modeling prompts.

Example Prompt Template

You are a helpful and fair assistant. Evaluate the following two responses to the user query. Pick the one that is more relevant, helpful, and correct.

User Query:

Response A:

Response B:

Which response is better? Answer with 'A' or 'B' and explain briefly.

Business Example

💼 Enterprise Chatbot Evaluation: A tech company tests three different LLM providers for their internal support bot. Instead of manually reviewing thousands of outputs:

- GPT-4 is prompted to judge outputs in a pairwise manner

- It selects the best response and explains its reasoning

- Results are aggregated to guide model selection for deployment

Limitations

- Evaluator bias: Models may favor longer, more verbose, or syntactically polished outputs even if they’re incorrect.

- Self-consistency: Same prompt may yield different ratings on different runs.

- Lack of ground truth: You are trusting the evaluator to be right, which isn’t guaranteed.

- Gaming risk: Models may optimize for what the evaluator likes rather than what users need.

When to Use

- For rapid model comparisons at scale (e.g., during A/B testing or fine-tuning loops)

- When human evaluation is too expensive or time-consuming

- In leaderboard-style benchmarks like LMSYS Chatbot Arena

- As a pre-filter before conducting smaller human evaluations

Best Practices

- Use multiple evaluator prompts to reduce bias

- Use temperature=0 to ensure consistent judgments

- Mix in a small set of human-labeled samples to calibrate and validate the LLM-as-a-Judge results

- Consider using chain-of-thought prompting to elicit better reasoning

7. Span-Level F1

What It Is

Span-Level F1 measures how well a model extracts specific spans of text by combining precision and recall into a single score. It’s commonly used in tasks like Named Entity Recognition (NER), extractive Question Answering (QA), and information extraction.

Rather than checking if the entire sentence is correct, Span-Level F1 focuses on whether the specific parts of interest (spans) are correctly identified.

Intuition

You want your model to extract correct spans (like names, dates, or answer phrases). Precision tells you how many of the spans your model predicted are correct. Recall tells you how many of the correct spans were found. F1 balances the two, high F1 means your model is both accurate and comprehensive.

Formula

\[F1 = 2 \cdot \frac{\text{Precision} \cdot \text{Recall}}{\text{Precision} + \text{Recall}}\]where

- Precision: The proportion of predicted spans that are actually correct.

- Recall: The proportion of actual (gold) spans that the model successfully predicted.

-

True Positives (TP): Correctly predicted spans (exact match with reference)

-

False Positives (FP): Spans predicted by the model but not in the reference

-

False Negatives (FN): Spans in the reference that the model missed

F1 ranges from 0 (no correct predictions) to 1 (perfect match).

How to Test It

- Annotate your dataset with span-level ground truth (e.g., using BIO tagging or character offsets).

- Run your model to extract spans from the input text.

- Compare predicted spans to ground truth: Count True Positives, False Positives, False Negatives.

- Compute precision, recall, and F1 using the formulas above.

Libraries like seqeval, scikit-learn, and HuggingFace evaluate can automate this.

Business Example

🔐 PII Extraction in Customer Support: A company wants to automatically redact customer PII (like email addresses, phone numbers, and account IDs) from incoming emails.

- Ground truth: Annotated spans showing where the PII occurs

- Model output: Predicted redaction spans

- Span-Level F1 evaluates how precisely and completely the model identifies sensitive data

Limitations

- Requires high-quality annotations at the span level, which can be labor-intensive.

- Sensitive to boundary errors: if the span is almost correct but slightly off, it is penalized.

- Doesn’t work well for free-form generation; only for structured extraction.

When to Use

- NER (Named Entity Recognition)

- Extractive QA (e.g., find answer spans in documents)

- Document parsing (e.g., key-value pair extraction)

- Medical, legal, or financial data extraction

8. Faithfulness / Groundedness

What It Is

Faithfulness (also known as groundedness) measures whether a model’s generated output is factually supported by a given context or source material. It’s especially important in Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) systems, where models are expected to generate answers based on retrieved documents.

A response is considered faithful if:

- It makes no claims that are contradicted by the source.

- Every factual claim can be traced to an external or retrieved piece of evidence.

Intuition

Faithfulness goes beyond fluency or relevance. A fluent answer may sound good but still hallucinate facts. Faithfulness ensures that what the model says is verifiably grounded in the source documents.

How to Test It

There is no single formula, but here are common methods:

1. Human Annotation

- Human reviewers compare generated output against source material.

-

Labels:

- Faithful: All claims are supported by the source.

- Unfaithful: Some claims contradict or are missing from the source.

2. LLM-as-a-Reviewer

- Prompt another LLM to compare output and source.

- Ask it to identify unsupported claims, contradictions, or hallucinations.

3. Binary / Scale-based Evaluation

- Binary (Faithful vs. Unfaithful)

- Scales (e.g., 1–5 for “degree of grounding”)

4. Fact Matching or Evidence Tracing (if structured references exist)

- Map each sentence in output to a source citation.

- Score coverage and alignment.

Symbolic Representation (Approximate Heuristic)

While there’s no official formula, a conceptual score could be:

\[\text{Faithfulness Score} = \frac{\text{Number of supported claims}}{\text{Total factual claims in output}}\]where:

- Supported claims: Claims verifiable from the provided context

- Factual claims: Statements that assert specific facts

This can be applied in automated or manual workflows.

Business Example

🏛️ Chatbot Compliance in Enterprise IT: A chatbot provides answers based on internal policy PDFs.

- Query: “Can I install third-party apps on my work laptop?”

- Ground truth: Policy doc says “Only apps from the internal catalog are allowed.”

- Model output: “You are allowed to install third-party apps.”

This output is unfaithful and could cause a policy violation. Evaluating faithfulness helps ensure compliance and trust.

Limitations

- No standard benchmark or metric: Unlike BLEU or F1, faithfulness lacks a universal quantitative score.

- Subjectivity: Human evaluations can vary.

- LLM evaluators may hallucinate: They may miss subtle contradictions or falsely confirm unsupported claims.

When to Use

- In RAG pipelines (e.g., document QA, chatbot over knowledge base)

- Legal, healthcare, and financial applications where factual grounding is essential

- Enterprise AI where models are expected to stick to known policies or documents

- Academic summarization or report generation from citations

Best Practices

- Highlight factual claims in output and require citation mapping

- Use human-in-the-loop workflows for critical domains

- Train models on contrastive examples (faithful vs unfaithful)

- Incorporate retrieval confidence signals

9. nDCG / MRR

What They Are

Both nDCG (normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain) and MRR (Mean Reciprocal Rank) are standard metrics for evaluating ranking quality , particularly useful for systems that return ranked lists such as search engines, recommendation systems, and RAG retrievers.

- nDCG measures how well a model ranks relevant results, taking both relevance and position into account.

- MRR focuses on how early the first correct item appears in a ranked list.

Intuition

Imagine a search engine returns a list of 10 items. Even if all the right answers are there, placing the most relevant ones at the top is crucial. nDCG rewards systems that put the most useful results earlier in the list. MRR is simpler: it just cares about where the first correct answer is.

nDCG Formula

\[nDCG@k = \frac{DCG@k}{IDCG@k} \quad \text{where} \quad DCG@k = \sum_{i=1}^{k} \frac{rel_i}{\log_2(i + 1)}\]where

- \(k\): The cutoff rank, e.g., nDCG\@10 only considers the top 10 results

- \(rel_i\): The graded relevance score of the item at position \(i\)

- \(DCG@k\): Discounted Cumulative Gain, which adds up the relevance scores, discounted by position

- \(IDCG@k\): Ideal DCG, which is the DCG if the system had returned items in perfect order

nDCG ranges from 0 to 1, with 1 meaning perfect ranking.

MRR Formula

\[MRR = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \frac{1}{rank_i}\]where

- \(N\): Number of queries or users

- \(rank_i\): The position (rank) of the first correct/relevant result for query \(i\)

If the correct result appears at rank 1, the score is 1. If it appears at rank 5, the score is 1/5. The MRR is the average across all queries.

How to Test It

- Use a dataset with ground-truth relevance labels for each query.

- For each query, have the model return a ranked list of items (documents, passages, FAQs, etc.).

- Assign relevance scores to each item in the list.

- Compute DCG, IDCG, and nDCG, and/or MRR based on where the first correct answer appears.

You can use libraries like scikit-learn, evaluate, or TREC_eval.

Business Example

🔎 FAQ Retrieval in Customer Support: A business uses an LLM-backed search to return the top 5 most relevant FAQ articles for a customer query.

- Relevance scores are labeled based on past user clicks or expert judgment.

- nDCG is used to measure if the best answers are near the top.

- MRR is used to check if the first correct answer appears early in the list.

Limitations

- Requires annotated datasets with graded or binary relevance labels.

- Sensitive to subjective judgments of relevance.

- MRR assumes there’s only one correct answer per query , not ideal for multi-answer problems.

When to Use

- Evaluating RAG retrievers and semantic search components.

- Ranking systems in recommendation engines.

- Optimizing LLMs that rank citations or knowledge snippets.

- When ranking position and user relevance are critical for task success.

10. Hallucination Rate

What It Is

Hallucination rate refers to the percentage of model outputs that contain factually incorrect, fabricated, or unsupported claims, particularly in contexts where the model is expected to generate outputs based on verifiable knowledge (e.g., from retrieved documents or structured databases).

This metric helps assess the factual reliability of generative models.

Intuition

Even if an output sounds fluent or well-structured, it may invent names, dates, citations, or facts that aren’t supported by any source. This is known as a hallucination. Tracking the hallucination rate helps quantify the risk of such errors in real-world deployments.

Approximate Formula

\[\text{Hallucination Rate} = \frac{\text{Number of hallucinated outputs}}{\text{Total number of evaluated outputs}} \times 100\%\]where

- Hallucinated outputs: Responses containing at least one incorrect or unverifiable factual claim

- Evaluated outputs: The total number of model responses that were examined (manually or automatically)

The rate is typically expressed as a percentage.

How to Test It

-

Manual Annotation (Gold Standard):

- Human reviewers compare generated output with source/reference documents.

- Each response is labeled as faithful or hallucinated.

-

LLM-Based Fact-Checking:

- Use a second LLM to identify and verify factual claims.

- Prompt it to mark which claims are unsupported or false.

-

Entity Matching / Fact Retrieval (Structured Data):

- Compare outputs against known facts in databases (e.g., Wikidata, product catalogs).

-

Scoring Granularity:

- Binary (Yes/No)

- Fraction of hallucinated sentences/claims per output

Business Example

⚖️ Factual Quality in Legal Summarization: A law firm uses an LLM to summarize contracts. Some generated summaries invent obligations or clauses not found in the original document.

- Annotators manually label summaries with hallucinations.

- Hallucination rate is tracked across versions of the model.

- Goal: Reduce hallucination rate below 5% before production deployment.

Limitations

- Labor-intensive: High-quality manual annotation requires time and domain expertise.

- LLM judges may hallucinate themselves.

- Hard to detect subtle errors: Some hallucinations are small but impactful.

- Subjectivity: Grounding may depend on what is considered a verifiable source.

When to Use

-

In high-trust domains where factual correctness is critical:

- Legal and compliance

- Healthcare and clinical documentation

- Financial reports or investment research

- Academic or government summarization

-

In Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) applications to ensure outputs are grounded in retrieved context

Best Practices

- Combine manual and automatic evaluations

- Use claim extraction to analyze hallucinations at sentence or clause level

- Audit hallucination types (e.g., fabricated entities vs. misleading numbers)

- Incorporate hallucination feedback into fine-tuning or rejection sampling pipelines

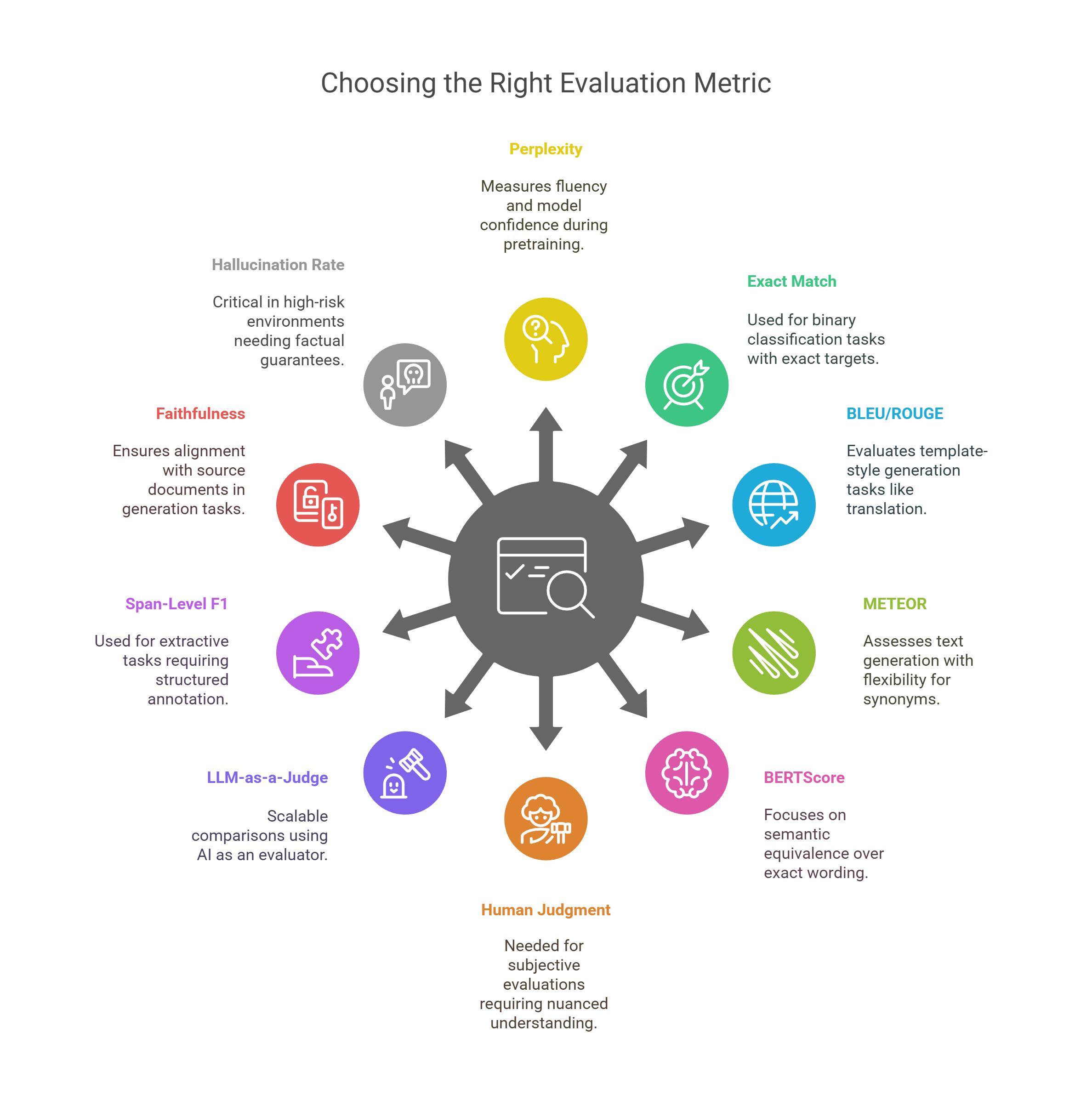

TL;DR: When to Use Each LLM Evaluation Metric?

Below is a quick-reference table summarizing 10 essential LLM evaluation metrics and the ideal scenarios for their application. Use this table to guide your evaluation strategy across generative, extractive, and retrieval-augmented tasks.

| Metric | Best When To Use | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Perplexity | Measuring fluency and model confidence during pretraining or fine-tuning | Comparing base model performance on internal corpora |

| Exact Match (EM) | Binary classification/extraction tasks with exact targets | Invoice number extraction |

| BLEU / ROUGE | Template-style generation (translation, summarization) | Product description generation |

| METEOR | Text generation with flexibility for synonyms and word order | Summarization evaluation allowing for lexical variation |

| BERTScore | Semantic equivalence matters more than exact wording | Paraphrase detection or answer alignment |

| Human Judgment | High-stakes or subjective evaluation requiring nuanced, contextual understanding | Legal summarization, creative content generation |

| LLM-as-a-Judge | Scalable comparisons or preference rankings during iteration | A/B testing two model outputs using GPT-4 as an evaluator |

| Span-Level F1 | Extractive tasks requiring structured span annotation | Named Entity Recognition, PII redaction |

| Faithfulness | RAG, policy-aligned, or document-grounded generation | Enterprise chatbot constrained by internal policy PDFs |

| Hallucination Rate | High-risk environments needing factual guarantees | Legal, healthcare, or financial summarization applications |

Notes:

- For end-to-end LLM applications, use a combination of task-specific and holistic metrics (e.g., BLEU + Faithfulness + Human Judgment).

- Where possible, pair automated scoring with human review to validate alignment with business requirements.

- Many modern workflows now incorporate LLM-as-a-Judge as an efficient pre-screening step before human evaluation.

Conclusion

LLM evaluation is a multi-dimensional task requiring both quantitative rigor and qualitative insight. No single metric suffices for all cases. The best practice is to combine multiple metrics, automated and human-driven, based on your application’s needs. As LLMs evolve, so must your evaluation strategy. Understand the tradeoffs, invest in tooling, and keep the feedback loop open between engineering, product, and compliance teams.

For further inquiries or collaboration, feel free to contact me at my email.